Odyssey: A long and adventurous journey or experience.

Homer wrote the epic poem The Odyssey 700 years before Christ was born. Poor Odysseus is beset by many challenges as he wends his way home after the Trojan Wars. The theme of a hero’s homeward journey of discovery has been reimagined many times since Homer. James Joyce echoed the themes as his hero Ulysses negotiated life in Dublin at the turn of the 20th Century. The Cohen Brothers rewrote the story in their film O Brother Where Art Thou? in the year 2000. Themes from the story have been reworked many times.

Our family experienced an odyssey for fourteen months, driving across the U.S. in 1984-1985, an adventure of a lifetime. I wrote a little about that trip in my blog post Technology for the Baby Boomer. Our grandson, born twenty-three years later, led me into another Odyssey. He came home from kindergarten one day and told his mother he wanted to join a group called Odyssey of the Mind. She asked what it was, and he told her there was a meeting of parents to learn about it that he wanted her to attend. She enlisted Ken and I to go along. A teacher from school explained the program which is an annual international problem-solving tournament for kids from kindergarten through college. They compete according to grade level. At last count, twenty-five countries participate.

The motto of OM is that for every problem, there is a solution. They believe learning should be fun and that there are always new uses for old items. The idea is to encourage creative problem-solving. The simplest explanation of the program is that each year, there are five categories of challenges issued by the International Odyssey of the Mind Association. Within each category are six problems to be solved. A team of five to seven kids chooses their problem and they work from October to February to come up with a solution that is presented to judges in late February at the first of three competitions. Teams are created by an Odyssey coordinator at the school. Team meetings are as often as the coach and kids decide, generally starting at once a week and becoming almost daily toward the end of the five months. In that time the kids conceive a solution to the problem they choose, create a script/story to explain their solution, each team member assumes a role, makes their own costumes and props, create a set that can be constructed on stage within perimeters set by the rules, and present the solution to the judges in an eight-minute skit. Easy? Not so much.

Adults are not allowed to assist in ANY portion of the process. Teams are penalized if a mom or coach even brushes someone’s hair before the performance. Any suggestion is automatically discarded if it comes from someone outside the team. The team takes great pride in not sharing their story or their work with anyone until the dress rehearsal when families are invited to preview their performance. In elementary school, the costumes were cobbled together with items found at Goodwill or in the back of closets. Tape, glue, and staples were used in the construction of costumes since none of the kids could sew. An adult is allowed to show the team how to use certain tools. Ken helped them learn how to use power tools safely, but we could only watch as they used them.

A coach’s job is to guide the kids, not with ideas, but with questions such as “what if…? How would you make or do that? How could you tell that story? How can you adapt an item or make something to do that job? How can you make that funny or more interesting?” The adult coach may NOT offer solutions during the creative process, only guidance in following the rules of the program. There is a whole book of rules aimed at keeping competition fair. As the team starts developing their solution, the coach asks if they are on track to answer the problem and if the plan can be performed on a stage twelve feet by fifteen feet. As I said, this is an international competition. It is judged at a world final in March of each year. Each team enters a local competition, then if they are chosen first or second place, they enter a state competition and finally, if they win, they are invited to the world competition where they meet teams from all over the globe who have won their divisions. A spontaneous competition is held on the same day as the skit competition. Each team is taken into a room without their coach and given a problem they must solve in ten minutes. That instant problem-solving skill is practiced throughout the year as the team works on their big presentation. Creative thinking, team building, and cooperative problem solving are skills that people need throughout their lives. Odyssey of the Mind builds great problem solvers.

Since our daughter was a single mom and full-time breadwinner, she did not have time to be a coach. Henry turned to me. “Grandma”, says he, “will you be a coach?” Can I turn down any request by my grandson? So I became a coach. I jumped in with both feet, having no idea what I was doing or what I would learn along the way. I fell in love with the competition and with each one of my team members. I coached four different teams in four years through four very different problems. It was a true odyssey – a journey of discovery. One year, Henry did not participate so I volunteered as a judge at the local competition. I learned how very inventive young minds are. If adults are not directing them, the sky is the limit. Adult minds can put brakes on imagination. The kids come up with amazing, creative solutions, costumes, props, and backdrops on their own – beyond anything I could imagine.

A month before competition each year I was sure my team would not be able to complete their task because something was missing in their presentation. I felt they were sailing their ship right off the edge of the earth. I racked my brain for strategies to help them find their way from the brink and stood helplessly watching the disaster unfold. I read and reread the rules to them, asking them to reevaluate their presentation. Each year they continued to work diligently toward the goal. They didn’t seem to feel the pressure. I didn’t sleep the whole week before the competition, knowing how disappointed they would be to not complete their task after all the time spent on it. I was riddled with anxiety, reevaluating each step in their progress. Each year, they proved me wrong. They found a way to make it happen every time. They always surprised me. At the end of each competition, I was in awe of my team’s abilities. By the fourth year, I learned to relax and have complete confidence in the team.

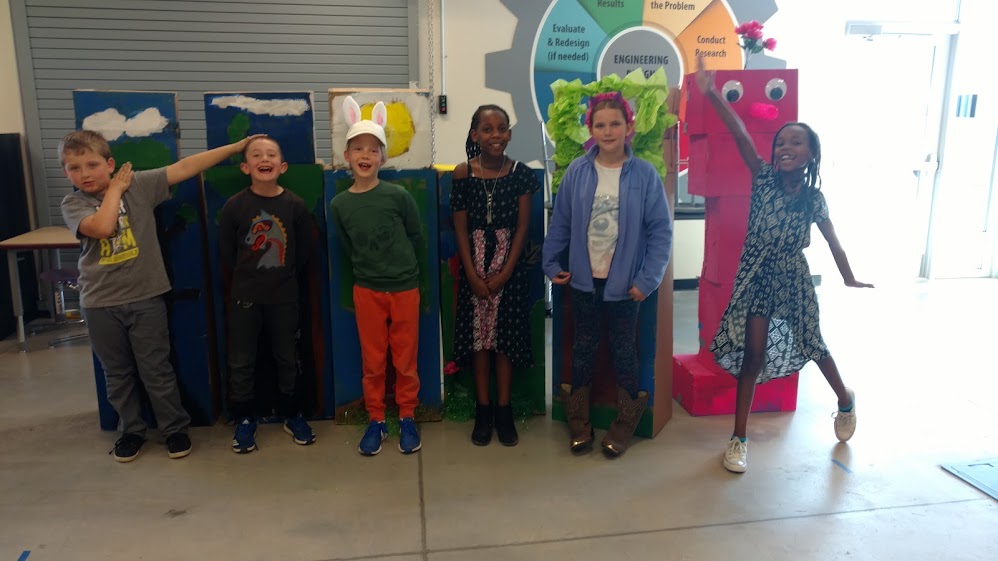

In 2018 the team, Team Wonder, did a presentation taking the Alice in Wonderland story in a new direction. They created a newscast that included an interview with the White Rabbit and the Cheshire Cat. The question was who stole the Queen’s tarts with the flamingo as the hidden camera. They had a news anchor, an interviewer, the White Rabbit and Cheshire Cat, a flamingo, and a commercial pitchman selling Wonka bars. It was hilarious.

One year the team came in third in the OM local competition and didn’t get to go on to state. Their problem was to recreate Leonardo Da Vinci’s workshop and conceive a new invention Leonardo may have devised. Their story took place in two time periods, modern daand the 1400’s. They had so much fun with their skit they begged me to ask if they could present it to the school at an assembly. I asked the principal who said she would consider it. The auditorium had many uses. It was occupied most of each day. Assemblies were carefully scheduled, and it was near the end of the school year. Finally. the last week of school the principal agreed to let the team make the presentation. She said it would not be a mandatory assembly, so each teacher had discretion about bringing their classes. My team was over-the-moon excited. Ken and I hauled all the costumes, props, and set fixtures (mostly made of cardboard) to school. It had been two months since the OM competition, and they had not had a practice. We did one practice session before the assembly. I told them they might have only a few in the audience. As the auditorium began to fill we realized that most of the school came. I sat in the audience to watch not knowing how it would go after so much time passed. The team got on stage and recognized they were not bound by the eight-minute time limit. They began to riff and improvise on their skit. I looked at Ken in astonishment. They were having so much fun. The applause was loud, and the kids were in their glory. They may have been third in the official competition, but they won the hearts of their schoolmates.

The last year that I coached, the team chose to solve the heretofore unsolved mystery of the Mary Celeste, a ship that was found in 1872 abandoned in the Atlantic without its crew, but otherwise intact with its cargo. What happened to the crew? They created the Thinkerton Detective Agency to investigate and find an answer. At the end of five months of hard work, the team presentation was timed at nine minutes. They tried and tried to do it faster, to get it shorter. No amount of magical thinking could change the clock. Teams are penalized for each second over eight minutes and it will generally take a team score out of contention. Dress rehearsal the night before competition was a calamity. My cousin, a school teacher, was visiting and watched the preview. She shook her head and looked at me. “How are they going to get this together?” I just smiled knowing that somehow they’d pull it off. I won’t say there weren’t tremors in my gut, but I had learned to ignore them. Early on the morning of competition, we gathered at the high school where judging took place, and they went over their skit in the parking lot – still over time. Right then and there they decided what to take out. They improvised a new script, they practiced twice, and it came in under eight minutes. They presented their improvised story at the competition. Of course, the judges would never know it was not the original script. At the beginning of their skit, a part of the backdrop/scenery broke, and they had to repair it on the fly. I caught my breath. They prepared in advance for mishaps by having extra parts, tape, scissors, and wire available on set. It was a true example of preparation and situational spontaneous problem solving just like MacGyver– exactly what Odyssey of the Mind teaches. Seamlessly, repairs were made and the skit continued without pause. They won the competition.

Our team was invited to the state competition. It was the beginning of covid and the tournament was in chaos because it is a hands-on, in-person event. Rules changed, everything changed, and the judging was to be by video. The team chose not to participate. They took their win and trophy for the school.

I am forever grateful for the time I spent with all the children I coached in Odyssey of the Mind, they were my teachers. I know each of them will be better equipped for their future after participating in OM, learning the tools of creative problem-solving.

I think of life as my soul’s odyssey through this earthly existence on its way home. We all have adventures and challenges along the way. At this point I can look back and see how very fortunate I am. My life has been fulfilling and good times are abundant, but I’ve come to realize that it is during the tumultuous times that the most valuable lessons are learned. No one gets out alive so enjoy the voyage and pay attention to the lighthouses along the way that guide you through rough seas and through the shoals.